July 31, 2006

Some time ago I was asked to write an essay for a quarterly publication called “Suffering” on the subject of “Music and Suffering.” This periodical is published by Stauros U.S.A., a non-profit organization founded by the Congregation of the Passion in 1973. Its mission statement reads as follows: “Stauros” is the Greek word for “cross.” Central to our mission is remembering the sufferings of Christ as a powerful paradigm for interpreting God’s action in the world. From this foundation, we reach out as an ecumenical, interreligious organization to empower all of us, no matter our faith or nationality, to find meaning, hope, and peace within the mystery of suffering. Stauros addresses both the physical and spiritual needs of those who suffer, working together so that faith is strengthened and hope flourishes.

Here is my essay.

Both the words “music” and “suffering” embrace definitions, thoughts, ideas, and nuances large enough to have given birth to thousands of books, lectures, pieces of art, films, sermons and concerts. There has been an endless array of attempts made by the wise and thoughtful to elucidate these subjects that touch every human experience. How can one person with one experience add to this? This question, particularly when focused on myself, seems foolish when held to the comparative narratives of greatness – both in musical perception and in suffering. Only when it can be placed as a small piece in the mosaic of understanding can such an undertaking be logically pursued.

“I’ve been asked to write about ‘Music and Suffering,’” I said to my husband, “What do you think about that?” “I certainly can relate to that,” he replied fervently, “I know I’ve suffered through a lot of music in my day.” That made me smile, but I quickly clarified. “That is missing the point entirely” I said, and proceeded to explain more fully the concept as I understood it, and he conceded that yes, he had shot wide. I did not need to point out to him that he too has joined my new life’s experience with an incurable disease in a most immediate way. Sickness of the blood is so very intimate. You can’t wad up the evil thing into a tumor or lump or breast or kidney or eye. Blood is essential, and mine seems hopelessly flawed. When the white cells diminished and diminished, this blood not only didn’t stop infections, it began to invite microbes and invaders to flourish. By itself the blood disease doesn’t cause pain or prickles, but it carries fear throughout the system. Fear of clotting – here today, tomorrow a vegetable, everybody’s nightmare – as close as the next heartbeat. Fear of infections, a scratch, red streaks away, fear. The pastor shook my hand yesterday in his finest greeting and I couldn’t wait to wash it with disinfectant.

“I’ve been asked to write about ‘Music and Suffering,’” I said to my husband, “What do you think about that?” “I certainly can relate to that,” he replied fervently, “I know I’ve suffered through a lot of music in my day.” That made me smile, but I quickly clarified. “That is missing the point entirely” I said, and proceeded to explain more fully the concept as I understood it, and he conceded that yes, he had shot wide. I did not need to point out to him that he too has joined my new life’s experience with an incurable disease in a most immediate way. Sickness of the blood is so very intimate. You can’t wad up the evil thing into a tumor or lump or breast or kidney or eye. Blood is essential, and mine seems hopelessly flawed. When the white cells diminished and diminished, this blood not only didn’t stop infections, it began to invite microbes and invaders to flourish. By itself the blood disease doesn’t cause pain or prickles, but it carries fear throughout the system. Fear of clotting – here today, tomorrow a vegetable, everybody’s nightmare – as close as the next heartbeat. Fear of infections, a scratch, red streaks away, fear. The pastor shook my hand yesterday in his finest greeting and I couldn’t wait to wash it with disinfectant.

The year is 1949, and it is a spring morning in the Confirmation Room of a white painted rural Lutheran school on an Iowa hill. The pastor is teaching a lesson on “suffering” which is never to be forgotten. This man has dark eyes, a thin moustache and the very black hair on his head is combed straight back from a widow’s peak. He has arrived at our out of the way rural parish because of a mysterious nervous breakdown having something to do with his chaplaincy in the Second World War. He is very intense and he has placed a crucifix on the table before us. Then he says something like this: “Our Lord Jesus Christ suffered and died for our sins . . . He was literally nailed up and hung there.” Our eyes are fixed upon the crucifix, which had the crown of thorns and the spikes in the hands and feet. The pastor looks at the five of us in that year’s confirmation class, and inquires, “Now, what does that mean to you, he suffered and died for your sins?” His voice is challenging, and we know that our answers had better be good. I still remember thinking that I hadn’t done anything that could possibly bring on such agony. “Your sins” he says again, implacably . . . I ventured that maybe what we did added up, like not obeying our parents or really, really wanting to hurt one of our brothers, and he said with approval, yes, exactly, and not only that, but every single sin that we would commit throughout our life, and every single sin that every single human would commit throughout their lives was punished right there on that cross. That was suffering, he told us, that was really suffering. We all sat and looked at the crucifix for what seemed like a long time. I believe I carried this measuring stick through the years, never applying the word or concept to any of my own life experiences. When contemplating this writing project, I asked a group of friends how they defined suffering. One said something like this: “Suffering is anything that carries you outside the place of your perception of well-being. It can range from uneasiness about something through the worst kind of agony.” This seems a good and complete definition with which to work. After thinking that I knew a lot more about music than suffering, within the week, I experienced an arterial blood clot in the kidney, which killed a third of the living tissue there because of a lack of blood. In this experience, there was and still is a great deal of physical pain. It was as though the moment I needed it, I was provided with a teeth-clenching, hair-pulling example of physical suffering, with a degree of mental anguish added in that the doctors said they had not seen anything like this before when dealing with my type of cancer, and therefore the possibility of it happening again, randomly and unexpectedly, became an added concern.

The year is 1949, and it is a spring morning in the Confirmation Room of a white painted rural Lutheran school on an Iowa hill. The pastor is teaching a lesson on “suffering” which is never to be forgotten. This man has dark eyes, a thin moustache and the very black hair on his head is combed straight back from a widow’s peak. He has arrived at our out of the way rural parish because of a mysterious nervous breakdown having something to do with his chaplaincy in the Second World War. He is very intense and he has placed a crucifix on the table before us. Then he says something like this: “Our Lord Jesus Christ suffered and died for our sins . . . He was literally nailed up and hung there.” Our eyes are fixed upon the crucifix, which had the crown of thorns and the spikes in the hands and feet. The pastor looks at the five of us in that year’s confirmation class, and inquires, “Now, what does that mean to you, he suffered and died for your sins?” His voice is challenging, and we know that our answers had better be good. I still remember thinking that I hadn’t done anything that could possibly bring on such agony. “Your sins” he says again, implacably . . . I ventured that maybe what we did added up, like not obeying our parents or really, really wanting to hurt one of our brothers, and he said with approval, yes, exactly, and not only that, but every single sin that we would commit throughout our life, and every single sin that every single human would commit throughout their lives was punished right there on that cross. That was suffering, he told us, that was really suffering. We all sat and looked at the crucifix for what seemed like a long time. I believe I carried this measuring stick through the years, never applying the word or concept to any of my own life experiences. When contemplating this writing project, I asked a group of friends how they defined suffering. One said something like this: “Suffering is anything that carries you outside the place of your perception of well-being. It can range from uneasiness about something through the worst kind of agony.” This seems a good and complete definition with which to work. After thinking that I knew a lot more about music than suffering, within the week, I experienced an arterial blood clot in the kidney, which killed a third of the living tissue there because of a lack of blood. In this experience, there was and still is a great deal of physical pain. It was as though the moment I needed it, I was provided with a teeth-clenching, hair-pulling example of physical suffering, with a degree of mental anguish added in that the doctors said they had not seen anything like this before when dealing with my type of cancer, and therefore the possibility of it happening again, randomly and unexpectedly, became an added concern.

That music works as a palliative to suffering is well known. How and to what degree this happens is totally subjective, so discourse about it must also be addressed subjectively. In this essay, I will explain how it is for me. The musical element of “melody” is defined as a series of tones that move forward in one of three ways: by repetition, by going upward in pitch by steps or leaps, or by going downward by steps or leaps. When I taught music to 7th Graders, I would play a game with them to demonstrate that each of us carries a large number of melodies within. For example, I would play “Name the Tune” and say. “Christmas song” then sound the first two tones of the carol, “Joy to the World”. Since all of us came from a like cultural tradition, one half or more of the children would guess the song on as little as two opening pitches. In this way I would show the class the miracle of a collection of large numbers of melodies in each of our heads, just waiting to be recalled. As years pass, melodies gather, stored behind doors of which we often are unaware. Then a certain scent, a south wind, a friend’s laugh – any unexpected thing can fling open that door and the song is there, waiting. It is waiting to come and help heal during times of suffering as well.

That music works as a palliative to suffering is well known. How and to what degree this happens is totally subjective, so discourse about it must also be addressed subjectively. In this essay, I will explain how it is for me. The musical element of “melody” is defined as a series of tones that move forward in one of three ways: by repetition, by going upward in pitch by steps or leaps, or by going downward by steps or leaps. When I taught music to 7th Graders, I would play a game with them to demonstrate that each of us carries a large number of melodies within. For example, I would play “Name the Tune” and say. “Christmas song” then sound the first two tones of the carol, “Joy to the World”. Since all of us came from a like cultural tradition, one half or more of the children would guess the song on as little as two opening pitches. In this way I would show the class the miracle of a collection of large numbers of melodies in each of our heads, just waiting to be recalled. As years pass, melodies gather, stored behind doors of which we often are unaware. Then a certain scent, a south wind, a friend’s laugh – any unexpected thing can fling open that door and the song is there, waiting. It is waiting to come and help heal during times of suffering as well.

A life time of playing hymns and teaching songs has provided me with a sizable collection from which to choose, and this music is as near as the next thought. When pain’s suffering is my human experience, there are songs bearing the poetry of psalmists and hymn writers to give me comfort. The miracle of music is that it can illuminate a deity as nothing else can. God is experienced by all of humankind, in some fashion, but God is experienced by each of us, one at a time, and uniquely so. Music is the same – its sounds are everywhere, impossible not to hear, but yet experienced by each of us, one pair of ears at a time and uniquely so.

A life time of playing hymns and teaching songs has provided me with a sizable collection from which to choose, and this music is as near as the next thought. When pain’s suffering is my human experience, there are songs bearing the poetry of psalmists and hymn writers to give me comfort. The miracle of music is that it can illuminate a deity as nothing else can. God is experienced by all of humankind, in some fashion, but God is experienced by each of us, one at a time, and uniquely so. Music is the same – its sounds are everywhere, impossible not to hear, but yet experienced by each of us, one pair of ears at a time and uniquely so.

Walking into the forest on a sunlit spring morning wondering why the disease has become the predominant shape and color of my day, I look upward to see two red tail hawks floating on the wind apparently just for the fun of it and the song, “Come away to the skies, my beloved, arise and rejoice in the day you were born . . .” sings loud and joyful. The creator God is near, the shapes and sounds of the natural world force the thoughts away from myself, reminding me that I am just a small gathering of tissues moving through a huge sphere.

When I was a director of music, I planned worship services and became very adept at timing hymns’ length, so I have a time clock already in place for a stanza of hymnody; for example, one verse of “In Thee is Gladness” lasts approximately 50 seconds, so I know that singing it through will take me past 50 seconds of present pain. The words will help me, “He sees and blesses in worst distresses, He can change them with a breath.” Perhaps I will sing it again and again, and so the journey through the valley moves forward. The doctor says, “This will hurt, but it’ll be over in 20 seconds.” I sing out loud so I can’t hear the sounds of the intrusion. “Have no fear, little flock, have no fear little flock. For the Father has chosen to give you the Kingdom, have no fear, little flock.” (Time – 18 seconds) “Do I need another verse?” I ask. “No, we’re done.” he says, and I am thankful. “Thankful hearts raise to God, thankful hearts raise to God, for he stays close beside you, In all things works with you; thankful hearts raise to God.” This time I am silent outside, but inside, the organ is full and children’s voices are loud and true.

When I was a director of music, I planned worship services and became very adept at timing hymns’ length, so I have a time clock already in place for a stanza of hymnody; for example, one verse of “In Thee is Gladness” lasts approximately 50 seconds, so I know that singing it through will take me past 50 seconds of present pain. The words will help me, “He sees and blesses in worst distresses, He can change them with a breath.” Perhaps I will sing it again and again, and so the journey through the valley moves forward. The doctor says, “This will hurt, but it’ll be over in 20 seconds.” I sing out loud so I can’t hear the sounds of the intrusion. “Have no fear, little flock, have no fear little flock. For the Father has chosen to give you the Kingdom, have no fear, little flock.” (Time – 18 seconds) “Do I need another verse?” I ask. “No, we’re done.” he says, and I am thankful. “Thankful hearts raise to God, thankful hearts raise to God, for he stays close beside you, In all things works with you; thankful hearts raise to God.” This time I am silent outside, but inside, the organ is full and children’s voices are loud and true.

There is music created during times of suffering, and when it is sent out into the world, it is there to aid and comfort the listener. Here is a story excerpted from a Minnesota Public Radio interview with Paul and Ruth Manz: One of the Manz’s children, their 3 year old son, came down with a childhood illness that threatened to end his life.

There is music created during times of suffering, and when it is sent out into the world, it is there to aid and comfort the listener. Here is a story excerpted from a Minnesota Public Radio interview with Paul and Ruth Manz: One of the Manz’s children, their 3 year old son, came down with a childhood illness that threatened to end his life.

“And at one point he was given up by the doctor as well as the staff,” Paul says. Paul and Ruth Manz took turns at their son’s bedside – Ruth by day, Paul by night. Ruth is a gifted lyricist and always on the lookout for ways to inspire her husband’s composing. “I’m the underling. She calls the shots,” Paul says, “In this particular case she was the spark plug…the spark plug that suggested the text,” he says. During their vigil Ruth brought Paul some words she’d crafted based on a text in Revelation.

“Peace be to you and grace from Him who freed us from our sins. Who loved us all and shed his blood that we might saved be. Sing holy, holy to our Lord, the Lord almighty God, who was and is and is to come, sing holy, holy Lord,” Ruth says.

“That is just a compilation of the theme in Revelation, Revelation 22, where it speaks of the longing of the Advent, actually, the coming of the Christ” she adds. “I think we’d reached the point where we felt that time was certainly running out so we committed it to the Lord and said, ‘Lord Jesus quickly come,'” Ruth says. “I made a sketch that night at the bedside and miraculously through prayer by a lot of people John survived,” Paul says.

That’s the story of the hymn, “E’n So, Lord Jesus, Quickly Come.” Ruth and Paul Manz’s son John is [now] in his 50’s and has the original score of the hymn written while he was ill.

This is an example of music born of suffering that brings joy to all who sing and hear it. This song has become popular not only throughout this country but also in other countries. There are countless musical compositions that have had their beginnings in such times that then await the needing listener’s ear.

Perhaps there are times and places in suffering where there is no song. A hymn writer paraphrases Psalm 137: “By the Babylonian rivers we sat down in grief and wept; hung our harps upon a willow, mourned for Zion when we slept.” I have always been struck by the finality of the image of hanging the harps in the willow trees by the river before crossing to the other side. No songs to take along into exile; in suffering, perhaps there are times when no song can be heard because we have been taken to the other side where the music is silent. I have not been there in my journey but the shadow of that possibility has been felt around the corners of my life experience. I walk and cry in the forest, and there is no music to be heard, for my fear is of the unknown. Death is waiting for all of us, but for me it has an immediacy that did not exist prior to my disease. All of the knowledge I have of love and peace, sensation and security, cherishing and being cherished, sheer joy and gaiety exists in the now, in this sphere. Great and generous gifts of God these have been, and though I want desperately to have the total trust that is so often spoken of in discourses on faith and God’s goodness toward us in all things, it is not yet complete, so I cry and I am still afraid and when that happens there is no music to be heard. Blessedly, the new day comes, the new sunrise brings light, and the songs begin again because hope is irrepressible. “Hope is the thing with feathers That perches in the soul. And sings the tune Without the words, And never stops at all.” Emily Dickenson

Perhaps there are times and places in suffering where there is no song. A hymn writer paraphrases Psalm 137: “By the Babylonian rivers we sat down in grief and wept; hung our harps upon a willow, mourned for Zion when we slept.” I have always been struck by the finality of the image of hanging the harps in the willow trees by the river before crossing to the other side. No songs to take along into exile; in suffering, perhaps there are times when no song can be heard because we have been taken to the other side where the music is silent. I have not been there in my journey but the shadow of that possibility has been felt around the corners of my life experience. I walk and cry in the forest, and there is no music to be heard, for my fear is of the unknown. Death is waiting for all of us, but for me it has an immediacy that did not exist prior to my disease. All of the knowledge I have of love and peace, sensation and security, cherishing and being cherished, sheer joy and gaiety exists in the now, in this sphere. Great and generous gifts of God these have been, and though I want desperately to have the total trust that is so often spoken of in discourses on faith and God’s goodness toward us in all things, it is not yet complete, so I cry and I am still afraid and when that happens there is no music to be heard. Blessedly, the new day comes, the new sunrise brings light, and the songs begin again because hope is irrepressible. “Hope is the thing with feathers That perches in the soul. And sings the tune Without the words, And never stops at all.” Emily Dickenson

Music is one of the conduits to the sacred sphere. When I am trapped within the body which is in the throes of pain or loss or change, sometimes the only way to endure, or to “pass through the valley of the shadow of death” is through the sounds of music. At such times one wants to plead with God first for surcease, if that is not possible, then for mercy, for strength or just endurance. When the thoughts are too plain and too near to help, it is a fine thing to recall a poet’s expressions carried on a composer’s melody. The music pulls God nearer to you, faith and trust in assistance from a greater power than your own can propel you forward into a place of survival. When we suffer, music can come to meet us and help us. . . it can come from within the great storehouse of songs that many of us hold inside, or from history or from newly composed works. It may come in the form of a Psalm where the very words sing, or in the melody of a musical written for Broadway. It may be instrumental, it may be tonal or atonal, it may be voices carrying wonderful texts or simply voices carrying melodies. Suffering is and will be a part of life, but at such times, music can strengthen and lift the heart. It can open perceptions of a God who is in every place – within, without, near as breath, yet vast as the universe. This is a gift of the Creator to humankind that can help and heal until such time when one joins in the making of the beautiful and perfect music that is sounding in God’s heavenly Kingdom, now and forevermore.

Music is one of the conduits to the sacred sphere. When I am trapped within the body which is in the throes of pain or loss or change, sometimes the only way to endure, or to “pass through the valley of the shadow of death” is through the sounds of music. At such times one wants to plead with God first for surcease, if that is not possible, then for mercy, for strength or just endurance. When the thoughts are too plain and too near to help, it is a fine thing to recall a poet’s expressions carried on a composer’s melody. The music pulls God nearer to you, faith and trust in assistance from a greater power than your own can propel you forward into a place of survival. When we suffer, music can come to meet us and help us. . . it can come from within the great storehouse of songs that many of us hold inside, or from history or from newly composed works. It may come in the form of a Psalm where the very words sing, or in the melody of a musical written for Broadway. It may be instrumental, it may be tonal or atonal, it may be voices carrying wonderful texts or simply voices carrying melodies. Suffering is and will be a part of life, but at such times, music can strengthen and lift the heart. It can open perceptions of a God who is in every place – within, without, near as breath, yet vast as the universe. This is a gift of the Creator to humankind that can help and heal until such time when one joins in the making of the beautiful and perfect music that is sounding in God’s heavenly Kingdom, now and forevermore.

+ + + + +

If you are interested in reading the other essays, subscription requests for Suffering: The Stauros Notebook can be directed to Stauros U.S.A., 5700 North Harlem Ave., Chicago IL 60631. Or you can contact them through E-Mail:

a m y @ s t a u r o s . o r g

or read more at www.stauros.org. Their fall publication will be “Worship and Suffering” and the winter issue is “Parish Community and Suffering.”

Today is a joyful day! Today is a splendid and wonderful day! Today we went to the oncologist’s office for the blood test, and for the first time, all of the readings were in the normal range. How beautiful is normal! The remission is still in place, and our doctor sat down to discuss how we would move on from here. He had already consulted with the doctor at the Med Center in Omaha who is recognized as an authority on MDS and they concluded that it would be a good thing to have remedial chemotherapy every eight weeks. He explained it this way: There is a material that wraps around the DNA, trapping it in a way that it cannot clone itself, or regenerate the new cells. The Vidaza therapy destroys this material, freeing the DNA to do its task. I appear to have enough stem cells remaining that my blood returned to normal counts. Since the stem cells have been under attack for an unknown amount of time, the number of them remaining is also unknown, so they think the safest route to remaining in remission is to repeat the chemotherapy enough to keep the blood cells at a normal level. The doctors felt that it would not be wise to wait until the blood cell levels dropped again before resuming treatment as that would signal more stem cells may have been destroyed, and bringing everything back would be more difficult. It was again explained to us that only the symptoms can be dealt with – the cause remains and its cure is unknown.

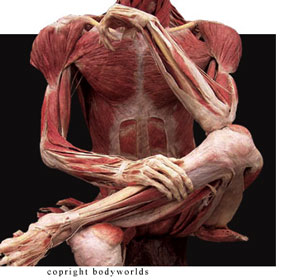

Today is a joyful day! Today is a splendid and wonderful day! Today we went to the oncologist’s office for the blood test, and for the first time, all of the readings were in the normal range. How beautiful is normal! The remission is still in place, and our doctor sat down to discuss how we would move on from here. He had already consulted with the doctor at the Med Center in Omaha who is recognized as an authority on MDS and they concluded that it would be a good thing to have remedial chemotherapy every eight weeks. He explained it this way: There is a material that wraps around the DNA, trapping it in a way that it cannot clone itself, or regenerate the new cells. The Vidaza therapy destroys this material, freeing the DNA to do its task. I appear to have enough stem cells remaining that my blood returned to normal counts. Since the stem cells have been under attack for an unknown amount of time, the number of them remaining is also unknown, so they think the safest route to remaining in remission is to repeat the chemotherapy enough to keep the blood cells at a normal level. The doctors felt that it would not be wise to wait until the blood cell levels dropped again before resuming treatment as that would signal more stem cells may have been destroyed, and bringing everything back would be more difficult. It was again explained to us that only the symptoms can be dealt with – the cause remains and its cure is unknown. A part of our adventure in Colorado has been good times with friends from Denver. When we first arrived at the beginning of our trip, they took us to the incredible Body Worlds2 at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. This is the exhibit where actual cadavers are shown in various action poses, all muscles, nerves, inner organs, brains – everything is exposed. For example, a human figure was shown kicking a soccor ball and two graceful skaters were displayed executing the Death Spiral. A German doctor by the name of Gunther von Hagens invented Plastination, the method of anatomical preservation that replaces bodily fluids and fat in donor specimens with reactive fluid plastics. Before the plastics harden, Dr. von Hagens fixes the bodies into dynamic, lifelike poses. Smoker’s lungs and black lungs of a coal miner (looking very much like lung shapes of coal) were also shown, as well as every part of the human anatomy, both in healthy and unhealthy states.

A part of our adventure in Colorado has been good times with friends from Denver. When we first arrived at the beginning of our trip, they took us to the incredible Body Worlds2 at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. This is the exhibit where actual cadavers are shown in various action poses, all muscles, nerves, inner organs, brains – everything is exposed. For example, a human figure was shown kicking a soccor ball and two graceful skaters were displayed executing the Death Spiral. A German doctor by the name of Gunther von Hagens invented Plastination, the method of anatomical preservation that replaces bodily fluids and fat in donor specimens with reactive fluid plastics. Before the plastics harden, Dr. von Hagens fixes the bodies into dynamic, lifelike poses. Smoker’s lungs and black lungs of a coal miner (looking very much like lung shapes of coal) were also shown, as well as every part of the human anatomy, both in healthy and unhealthy states. I was strolling through a shop in Aspen, and a little girl of about seven bumped into me as she briskly searched the designer racks – she yanked out a purple dyed suede leather mini skirt with fringe and held it aloft saying, “Mother, this is what I want.” The mother was two racks over, looking at shirts, and hanging on to the hand of a toddler who was playing with a shiny pink purse that had “Born to Shop” embroidered on the side of it, and her reply was, “ Why sweetie, that’s cute! Do you want to try it on?” It was really a garment designed for a small adult, but there you are.

I was strolling through a shop in Aspen, and a little girl of about seven bumped into me as she briskly searched the designer racks – she yanked out a purple dyed suede leather mini skirt with fringe and held it aloft saying, “Mother, this is what I want.” The mother was two racks over, looking at shirts, and hanging on to the hand of a toddler who was playing with a shiny pink purse that had “Born to Shop” embroidered on the side of it, and her reply was, “ Why sweetie, that’s cute! Do you want to try it on?” It was really a garment designed for a small adult, but there you are.  Yesterday evening we were walking on the cobbled main street of Vail when we met a young woman walking alone up the hill. She was a bit past ample in size, and wearing a simple black dress with super high heeled shoes. The cobbles made her progress precarious, and with a look of pain around the corners of her attempt to look upbeat, she winced a little with every foot fall. I couldn’t help but wonder what her destination might be, and I sent a silent wish that her hopes for the evening would be fulfilled.

Yesterday evening we were walking on the cobbled main street of Vail when we met a young woman walking alone up the hill. She was a bit past ample in size, and wearing a simple black dress with super high heeled shoes. The cobbles made her progress precarious, and with a look of pain around the corners of her attempt to look upbeat, she winced a little with every foot fall. I couldn’t help but wonder what her destination might be, and I sent a silent wish that her hopes for the evening would be fulfilled.  These past days have provided layers upon layers of experiences as we traveled to Colorado to spend time with our children and grandchildren at a lodge near Rocky Mountain National Park. There was the moment when we all gathered, safe and full of anticipation for the adventures ahead, and then the poignant scene of lining up waving and waving goodbye to John-paul, the first to leave the group. We ate together, laughed a great deal, and made a first acquaintance with the

These past days have provided layers upon layers of experiences as we traveled to Colorado to spend time with our children and grandchildren at a lodge near Rocky Mountain National Park. There was the moment when we all gathered, safe and full of anticipation for the adventures ahead, and then the poignant scene of lining up waving and waving goodbye to John-paul, the first to leave the group. We ate together, laughed a great deal, and made a first acquaintance with the  One of our events was a serendipitous decision to attend the Roof Top Rodeo at Estes Park where we watched a part of the cowboy’s folklore come alive in the bronco riding, the calf roping, and the Rodeo Princesses atop very beautiful horses, wearing glittering chaps, hats and shirts and repeatedly riding around the arena. Our granddaughters were enthralled. You could see the entire range of mountains from your seats and that was enhanced by a beautiful sunset reflecting upon huge cloud formations climbing up and over the peaks. With large sacks of $2.00 popcorn, the event was entirely memorable.

One of our events was a serendipitous decision to attend the Roof Top Rodeo at Estes Park where we watched a part of the cowboy’s folklore come alive in the bronco riding, the calf roping, and the Rodeo Princesses atop very beautiful horses, wearing glittering chaps, hats and shirts and repeatedly riding around the arena. Our granddaughters were enthralled. You could see the entire range of mountains from your seats and that was enhanced by a beautiful sunset reflecting upon huge cloud formations climbing up and over the peaks. With large sacks of $2.00 popcorn, the event was entirely memorable. After saying goodbye to the dear ones, we drove over three mountain passes to Aspen to listen to grand music at their well-known music venues, and we will conclude our summer odyssey at Vail listening to the New York Philharmonic playing summer concerts at the Gerald Ford Amphitheater located there. The unforgettable beauty of mountains and music helps to buffer the end of our long-awaited gathering and return to life “as usual”. All is well with health issues – so much so, it is easy to forget that they exist at all.

After saying goodbye to the dear ones, we drove over three mountain passes to Aspen to listen to grand music at their well-known music venues, and we will conclude our summer odyssey at Vail listening to the New York Philharmonic playing summer concerts at the Gerald Ford Amphitheater located there. The unforgettable beauty of mountains and music helps to buffer the end of our long-awaited gathering and return to life “as usual”. All is well with health issues – so much so, it is easy to forget that they exist at all.